Every few years we have this discussion about whether or not we are going to raise the debt ceiling. Let’s just be honest, the debt ceiling will be raised. Since 1960, it’s been raised 78 times (more than once a year). The chart below shows the times the debt ceiling has been raised since 1970.

The chatter about a potential default is just a charade. Politicians have kicked the debt limit can down the road 78 times in the past 63 years, so remember… this has happened before (as if basic math and the 14th Amendment don’t stand between the ceiling and default). The debt ceiling has always been mostly symbolic: Keep it or lose it, reach it or exceed it, it doesn’t change much for the US economy.

What is the Debt Limit?

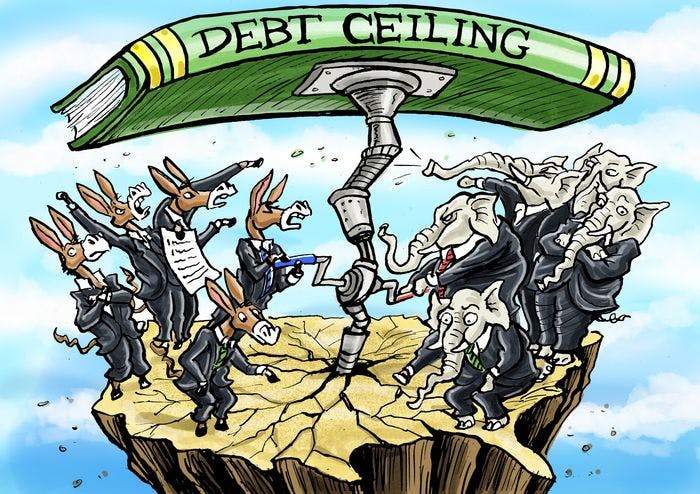

Per the Treasury, “the debt limit is the total amount of money that the United States government is authorized to borrow to meet its existing legal obligations, including Social Security and Medicare benefits, military salaries, interest on the national debt, tax refunds and other payments.” Today the debt ceiling is a political football that everyone loves to hate and fight over. Yet it wasn’t always so. When Congress conceived it, their goal was to make borrowing easier and less contentious. The first several increases were routine and not hard-fought. But in the mid-20th century, politicians discovered voters weren’t big on debt. Thus began the tradition of politicians using it as a bargaining chip and, later, tying other contentious measures to debt ceiling legislation in hopes of ramming them through when they might not otherwise pass. Our lawmakers just have a habit of waiting till the 11th hour (or later), for maximum dramatic effect.

What happens if they don’t raise it before the deadline?

Even if extraordinary measures and Treasury cash on hand ran out, it still wouldn’t mean default. Default is one thing and one thing only: failing to pay interest or repay principal on maturing debt. This is not a discretionary spending item. The 14th Amendment stipulates “the validity of the public debt … shall not be questioned.” In 1935, the Supreme Court interpreted this to mean Congress’s borrowing carries with it the “highest assurance [of payment] the government can give.”[i] In short, this means the US must honor its debt. If accounts payable exceed cash on hand in a given month, the Treasury can and must prioritize debt service above all others. As the Government Accountability Office declared in 1985: “The Secretary of the Treasury has the authority to determine the order in which obligations are to be paid should the Congress fail to raise the statutory debt ceiling and revenues are inadequate to cover all required payments. There is no statute or any other basis for concluding that the Treasury must pay outstanding obligations in the order they are presented for payment.”[ii] The United States pays its most important bills first, rather than pay as they come due.

Will Social Security checks stop with no settlement?

The US has plenty of money to service its debt, and then some. Monthly US tax revenue is more than high enough to cover monthly interest payments. In none of the past 12 months did monthly interest expense exceed monthly receipts. Monthly interest payments ranged from 8% to 31% of monthly tax receipts.[iii] This means revenues can cover bondholders, pay Social Security and Medicare benefits, and still pay other expenses.

Politicians are already perhaps zeroing in on a can-kick. If recent history is a guide, we believe they won’t act fast—not while it is a perfectly good stump issue for this summer’s Democratic primary debates. So get ready for what we believe will be some grandstanding and hyperbolic warnings of default—and be ready to tune it out.

[i] United States Supreme Court, Perry v. United States (1935) No.532, February 18, 1935.

[ii] United States Government Accountability Office, “Principles of Federal Appropriations Law,” Chapter 2, The Legal Framework, 2016 Revision. As of 6/14/2019.

[iii] Source: US Treasury Department, as of 6/17/2019. Monthly Treasury Statements, June 2018 – May 2019.

Thanks for this concise explanation of the debt ceiling!